"Papyri are the closest we get to the people of the Antiquity. Nowhere else do they emerge so vividly; people wrote down texts and recorded important life events on rolls and fragments of papyrus. When we study these fragments today, we get a direct view of everyday life in Egypt under Greek, and later Roman, rule", says Anastasia Maravela. The papyri in the University of Oslo Library collection are very diverse and include private letters, horoscopes, dinner invitations, culinary and medical recipes, school texts, marriage and divorce papers, arrest orders for tax evaders, accounts, death notices, fragments of literature, and an entire roll of magic formulas.

Maravela is Associate Professor in Ancient Greek, and is the first UiO scholar in many years to research papyri.

"UiO papyrologists were once considered among the best in the world. We are renewing that tradition, and have re-established UiO as an important centre for research on papyri from Egypt, with a great deal of important texts that have not yet been studied", she remarks.

UiO has the largest papyrus collection north of Berlin. The collection consists of nearly 2300 papyrus fragments, in addition to 27 ostracka (inscribed potsherds), some parchments, some text on mummy labels and one mummy-shroud.

How did so many papyri end up in Oslo? How did the academic papyrus research community become so strong in Oslo?

Klondike in Egypt

Let us step back about one hundred years. At the end of the 1800s, a "papyrus fever" raged in Egypt. The leadership of the country had decided that new farmland was to be cultivated, and the farmers knew where to find fertile soil, sebakh: on the outskirts of abandoned towns from Antiquity. This is where garbage had been disposed of, including papyri. The dry sandstorms (hamsin) that annually blow through Egypt brought sand from the desert and covered up the rubbish heaps, thus preserving the papyri. Papyrus was used for writing throughout the Mediterranean, but it is only in Egypt that it has survived, thanks to the dry sandy soil.

When the Egyptian farmers started to dig in the fertile soil for new fields, the intellectuals of Europe panicked: Antiquity is about to disappear! When the poor farmers understood the value Europeans placed on the papyri, they sold the texts willingly, often tearing the papyrus up to have multiple fragments to sell.

In Norway, the classical scholar Samson Eitrem (1872–1966) understood that this was a question of "now or never". He spent his honeymoon in Cairo, and used his own funds to purchase a number of papyrus fragments and potsherds with texts in ancient Greek in the antiquities market of the city. The year was 1910, and the papyrus collection at UiO had begun.

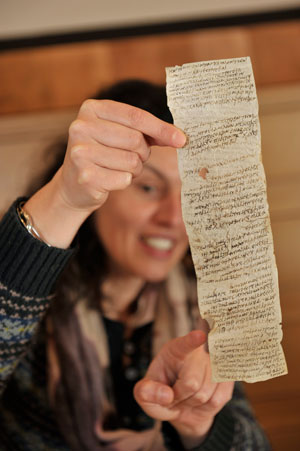

NOTES: Anastasia Maravela shows a parchment sheet containing notes that a Christian author made while writing a theological text. The papyrus is from the fifth or sixth century. (Foto: Francesco Saggio)

NOTES: Anastasia Maravela shows a parchment sheet containing notes that a Christian author made while writing a theological text. The papyrus is from the fifth or sixth century. (Foto: Francesco Saggio)

"Eitrem became a Professor of Classics four years later, and urged the University to make further purchases. In 1920, he travelled to Egypt again, and purchased approximately 500 papyri for the collection using funds from the University Anniversary Fund and the Nansen Fund. In the following years, Eitrem and his colleague Leiv Amundsen collaborated with the British Museum and a number of universities in the USA to procure more papyri. It is thanks to the decisiveness of these two men that we today are a renowned centre for papyrus research", Maravela states.

Homer, Plato and Matthew

The collection is kept in a dedicated room on the fourth floor of the University of Oslo Library (mezzanine level) at the Blindern campus. Many of the papyri in the collection are torn bits of the oldest European literature: The Iliad and the Odyssey by Homer, Orestes by Euripides and The Misanthrope (Dyskolos) by Menander. The collection also includes excerpts from Plato; a papyrus fragment with the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 11, verses 25-30 in a miniature codex used to protect its bearer; and and one of the oldest choral songs from a lost drama, including its musical score.

However, most of the papyri document everyday life in Graeco-Roman and early Byzantine Egypt. One of the really exciting fragments in this context is the world's oldest census declaration, which is from 34 CE.

"More or less every activity in Roman Egypt was taxed. Our census declaration, which gave the authorities the basis for demanding taxes, was submitted by a 35-year-old woman and covers all members of her household: herself and her five-year-old son. The woman is represented by a male relative who is her and her son's guardian", the papyrologist explains.

Erotic attraction

But the jewel of the collection is something else: a nearly 2.5 metre papyrus purchased by Samson Eitrem in Cairo in 1920. It is an entire roll of magic formulas to be used for various purposes.

"The papyrus is from the fourth century CE, and is one of the most important books of magic from Antiquity anywhere in the world. The roll contains 19 magic formulas for spellbinding the person on whom magic was exercised." One of the recipes details what one can expect from using it with particular clarity: "Magical recipe that constrains anger, ensures goodwill, brings victory in court. It even works on kings - there is none better!"

Seven of the recipes on the large papyrus on magic help the user win the partner he or she wishes to attract sexually, and these therefore have the heading agôgê, which means "spell for attraction". One of them starts like this: ''The best magical spell to set one on fire - there is none better. It attracts men to women and women to men, and makes virgins run away from home." A great deal of advice follows regarding what to do and say, and according to the text of the papyrus this is all very effective.

"There is even a birth control recipe in our papyrus, 'the only one that exists in the world' it says. This was a society without condoms, apparently, but it is doubtful whether magic could remedy that."

"In addition to the large papyrus on magic, there are another six 'magic' papyri in the Oslo collection. These contain various magic formulas and recipes in which specific demonic powers are called upon as part of the magic ritual. Eitrem was one of the first to emphasise the pervasive importance of magic during Antiquity. His work continues to be quoted and referred to in the modern academic debates on the topic", notes Maravela.

Christianity makes an impact

The researcher finds the Christian texts in the collection particularly interesting, and concentrates much of her research on unpublished Christian papyri. She shows us a papyrus with inventory number 1463, and reads: "'...receive in peace the persons who carry this letter, the young man (or slave) Artemidorus who is a believer, and Heracles who is undergoing catechism' (implicitly 'in the Christian faith'). This is a Christian letter of recommendation with ends with a long list of signatures ('I sign and confirm this'). A priest and a number of prominent persons, probably members of a Christian congregation, are among the signatories to the letter."

"The papyri usually have many holes, so it is necessary to read comparable texts to fill in what has been lost. I have transcribed the text to the best of my abilities, and compared it with other letters of recommendation on papyrus", says Maravela. It turns out that this fragment is unique, particularly because the list of signatories to the letter is unusually long.

This letter dates to the fourth century CE, and is among the earliest indications that Christianity is making an impact on society.

"It is very interesting to follow how Christianity spreads and see that the Christians appear as organised groups. Papyrologi expands our knowledge about Christianity as a historical phenomenon through new, original sources", says Maravela.

Games and learning

Maravela is also working on something that may be a school text. It consists of four groups of seven words. The words are all names of persons, each with three syllables. The names in each group start with one of the following letters: L, M, N and X, which in the Greek alphabet comes after N. Next to each name is a number that corresponds to the name's numerical value when all the letters have been added. In the Greek numerical system, each letter also corresponds to a number. Isopsephy, or finding the numerical value of a word, has up until now only been known from magic and religions in which numbers are written in place of holy names. For example, Christians wrote 99 instead of of “AMHN” (1+40+8+50), Maravela explains. Isopsephic poetry is also thought to have been a type of game. This new text, which might be an exercise developed by a teacher, shows that isopsephy may also have been used in an educational context.

"The exercise probably had two learning objectives: the students were to practise finding names with a specific number of syllables starting with a specific letter, and also practise adding. I cannot be entirely certain of my interpretation", Maravela notes, "because, as I mentioned, this text is unique". Another possible explanation for this text is that it is a private game.

Medical papyri

Maravela is participating in an international project, Corpus dei Papiri Greci di Medicina Online, which is creating a searchable database of all medical papyri in Greek worldwide, and a dictionary of ancient medical terminology. However, the database does not contain the medical texts from Antiquity that we know via manuscripts from the Middle Ages, such as the Hippocratic texts and the work of Galen.

"The database represents the first complete collection of medical works from Antiquity that had been thought to be lost until they were recovered, partly or entirely, through papyri. Our goal is to recreate the lost medical library of Antiquity", Maravela explains.

Medicine had a long tradition in ancient Egypt. During the Hellenistic period, but also in Roman times, Alexandria was an important centre for the study and practise of medicine. It is therefore natural that important medical texts were found among the papyrus fragments. For example, Erasistratus' writings on fever and Soranus' writings on gynaecology have been found in this way. "I have published two recipes for medicines for diseases of the eyes", the researcher notes.

The papyrus texts also shed light on medical practice. For example, medical recipes that people copied and brought to the chemist, or lists of ingredients needed to make a particular medicine. The latter are likely shopping lists. Maravela brings out a very small papyrus fragment.

"When I first looked at this, I thought this looks both difficult and insignificant. But once I had taken a closer look and deciphered the text to some extent, I understood that this was a very small square sheet of papyrus with recipes for eye salves, kollyria. There is one recipe on each side of the sheet. I was even more excited when I discovered that one of the recipes was for an eye salve advertised as 'so effective that it works within a single day'. We know that medicines with this level of effectiveness existed, but not that they were used by the people of Egypt. But now we know!"

Medical and other recipes and lists of ingredients on papyri tell us about the medicines, raw materials and foods used by people in their everyday lives, especially on the periphery of the Roman Empire. People kept the papyri in their pockets and took them to the chemist or the market to buy the ingredients. This type of papyri show us the ingredients and raw materials that circulated in Egypt at the time.

New insights

"The mystery surrounding the papyri is captivating. A fragment that seems in very poor condition may turn out to contain lost poetry. Papyri are original sources and are of great importance to philologists and historians of the ancient world. They often provide entirely new perspectives on Antiquity. We still have nearly 2000 papyrus fragments in Oslo that have yet to be edited and studied. They may reveal aspects of life in Antiquity that we did not know of previously", Anastasia Maravela says.